Acknowledgement of Country

We acknowledge the traditional owners of the lands on which this research report was completed, the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation, and pay our respect to their Elders past, present and emerging.

We value the spirit of reconciliation and recognise that any work to improve intersectional gender equality must acknowledge the inequalities that continue to be experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Working towards equity for all must begin with ensuring an equal voice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

As we strive for a more inclusive Australia, we acknowledge that sovereignty has never been ceded. This land always was and always will be Aboriginal land.

The aim of this report is to identify key issues for Women of Color’s lived experience with racism and harassment in the Victorian Public Sector, and to provide practical advice for Australian organisations on how to address racism, discrimination and bullying in the workplace.

The approach of this study involved 5 focus groups, survey data of 188 employees at VPS and thorough research on local and international reports and literature to explore how questions of racism were addressed in a global context.

The consulting team conducted five focus groups in this project – three with 17 volunteer Women of Colour participants employed in the VPS, and two focus groups with 25 managers and senior leaders in the VPS of multiple diverse backgrounds. The focus groups encouraged participants to share and discuss their personal views and experiences around racism and discrimination in their workplace.

Background

In 2019, CPSU conducted a conference and several workshops to understand the views of Women of Colour on workplace racism, discrimination, and violence.i The conference and workshops fundamentally found that racism and discrimination are major contributors to “poor workplace culture” and pose a significant barrier for Women of Colour in the workplace.

Thirty-two (32) percent of respondents to a pre-conference survey indicated that they had personally experienced workplace racism, and fifty-eight (58) percent of respondents had personally experienced bullying or harassment in the workplace. However, of those who indicated they had experienced workplace racism, sixty (60) percent chose not to report the incidents due to a range of barriers that will be covered in this report. Furthermore, those who did report suggested that reporting the issue did not lead to satisfactory follow-up actions. Instead, reporters commonly received no response, or some discovered later that the company had relocated the perpetrator(s) to another department. This approach is ineffective as it fails to address the underlying problem and places further burden on the victim. Informal resolution was the most common departmental response to dealing with complaints.

Other significant reasons for choosing not to report racism, discrimination and bullying were:

- A lack of trust in management to investigate and respond impartially.

- A lack of belief that reporting would help to change the situation.

- A view that speaking up would negatively impact the complainant’s career.

I wasn’t able to be included even when I’ve specifically asked for it, and I was kept in silence; I was told to do all the work without even knowing what it was for

Summary Analysis

The survey, interviews and focus groups identified major issues with racism, discrimination and harassment experienced by Women of Colour in the workplace. The major findings are summarised below.

Women of colour as susceptible targets of workplace racism and discrimination

Women of Colour regularly find themselves as a minority in the workplace, in most cases being both the gender and racial minority. Women of Colour face bullying resulting from the intersectional effects of both misogyny and racismii. A 2016 study titled “Bullying and Harassment in Australian Workplaces” found that women are “more likely to receive unfair treatment because of their gender”iii, and experience significantly higher levels and longer periods of bullying than men.

Focus Group Response

Focus group participants revealed some of the same experiential manifestations of racism towards Women of Colour as the 2016 study, including:

- Name-calling (Verbal Abuse)

- Unacknowledged work contributions (Work-related Bullying)

- Exclusion from social events and meetings (Social Isolation)

- Being blamed for somebody else’s mistake (Slandering Reputation)

- Facing hostile body language and/or tone of voice (Physical Intimidation)

- Bullying outside of the workplace – primarily on social media (Personal sphere)

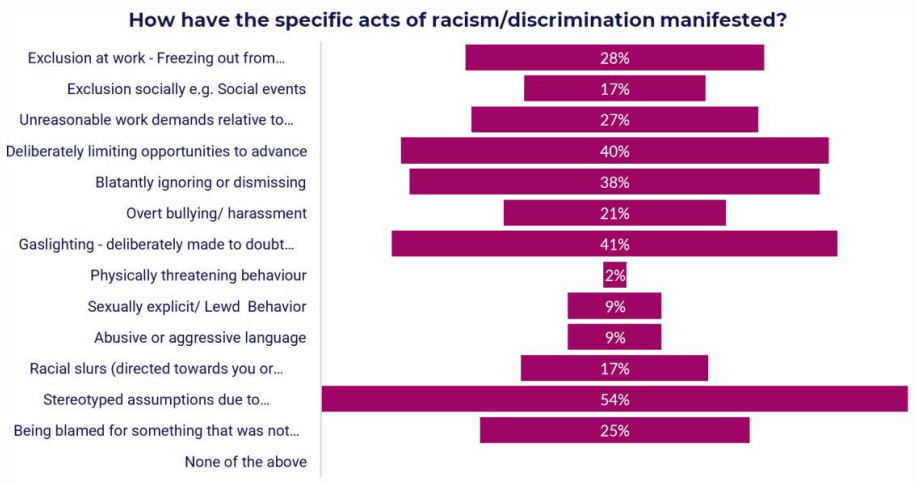

Survey responses for Woman of Colour were consistent with the focus group findings:

- Verbal Racial Abuse – 17 percent

- Exclusion from social events and meetings – 28 percent

- Being blamed for something that was not your responsibility – 25 percent

- Overt bullying and harassment -21 percent

- Gaslighting – 41 percent

The survey also identified 9 percent as having experienced sexually explicit behaviour which, while low in comparison to other experiences, it constitutes a form of discrimination that can inflict serious harm to the individual. Such behaviour can also cause significant damage to an organisation’s reputation if it escalates to the threshold of criminal behaviour.

Have you witnessed or directly experienced racism/discrimination at work?

76 percent of all respondents in the survey either witnessed discrimination, experienced discrimination, or had both witnessed and experienced it

“It’s hard at times when [Racism and Discrimination] is hidden, you always think if you’re making it up or blowing it out of proportion.”

What is the impact of systemic racism on you?

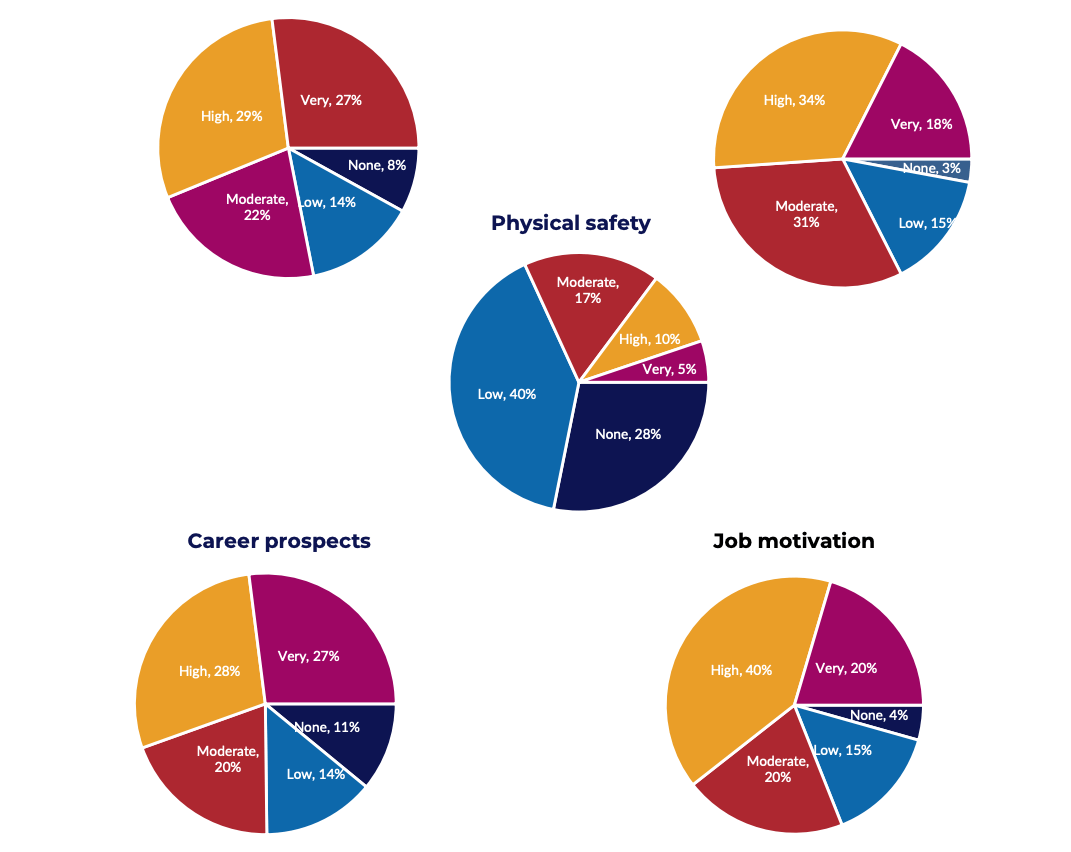

Consistently across all ethnic groups, more than 50 percent of respondents felt that the impacts of systemic racism were high or very high for their psychological safety, job motivation and career prospects. 15 per cent of respondents expressed concern for their physical safety.

15 percent of respondents being highly or very highly concerned about their physical safety is a significant percentage of the polled group, and warrants closer attention to avoid situations that may cause serious harm to the individual.

51 percent report being severely impacted by the effects of racism in terms of psychological safety, job motivation, and career prospects. These statistics reinforce the need to address racism and discrimination urgently to manage the harm caused

Focus Group Response

Focus group participants reported some of the following effects:

- Negative feelings towards going to work

- Unease participating and other work withdrawal behaviours12 (some mentioned others who had quit their job)

- Reduced job satisfaction and productivity making them feel unvalued

- Lowered self-esteem and confidence

- Changes in their outlook towards both current and future workplaces

- Feelings that they are unable to be themselves and to feel safe

“Acting manager was reluctant to lodge a report, system triggered a number of internal services contacting me but it was a simple ‘tick and flick’ exercise without any actual support to me.”

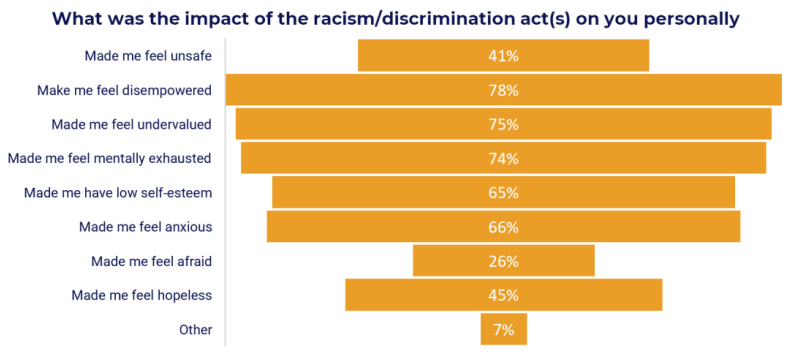

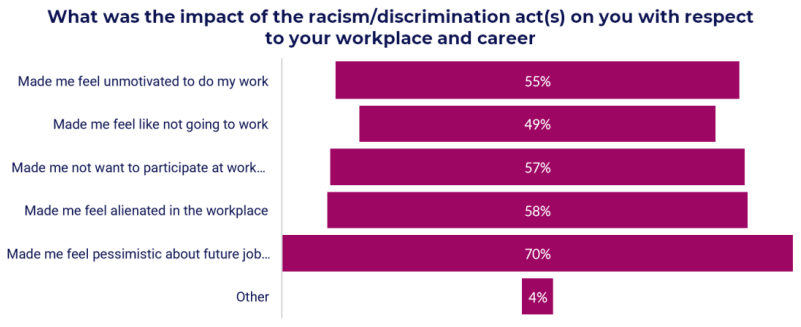

What was the impact of the racism/discrimination act(s) on you personally?

The majority of respondents to the survey, who had experienced or witnessed racism, discrimination or race-related bullying have also reported experiencing feelings of disempowerment (78 percent), anxiety (66 percent), and low self-esteem (65 percent) in line with these past studies.

Given the psychological impacts to the individual, organisation have a positive duty of care to ensure that the work environment is also safe from psychological hazards such as discrimination, racism, and race-related bullying. Furthermore, as indicated in the above chart, reducing the incident of racism and discrimination will improve employee motivation and productivity. A strategy to prevent racism and discrimination in the workplace, discussed later in this report, can reduce the incidence of such acts in the first place.

“Because it can be quite covert, it can be very micro in its form; it can cut you off from your peers and others. You don’t say it. And in speaking out, you know you are wrong”

Ease of reporting

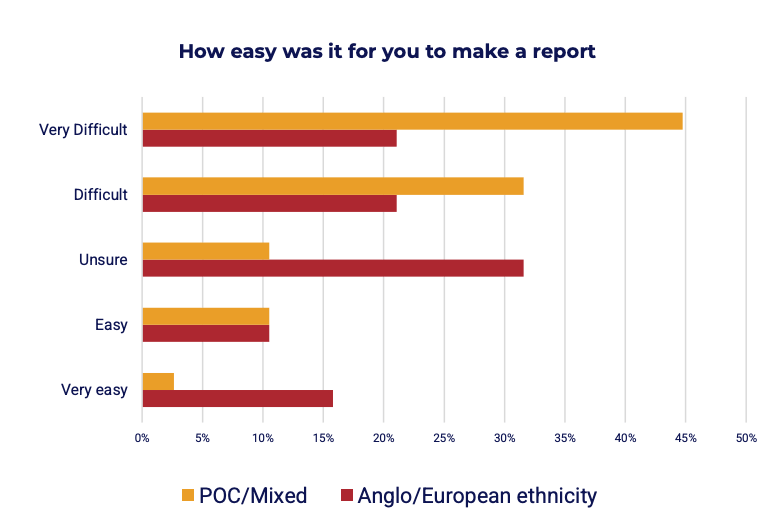

While the majority of all respondents found reporting difficult, 76 percent of people of colour respondents found reporting difficult or very difficult, compared with 42 percent of respondents with Anglo/ European ethnicity. Ensuring that the ability to report is accessible, the systems are trusted and understood by all, is critical to all employees engaging with the process and being willing to report either as witnesses or targets.

“Because it can be quite covert, it can be very micro in its form; it can cut you off from your peers and others. You don’t say it. And in speaking out, you know you are wrong”

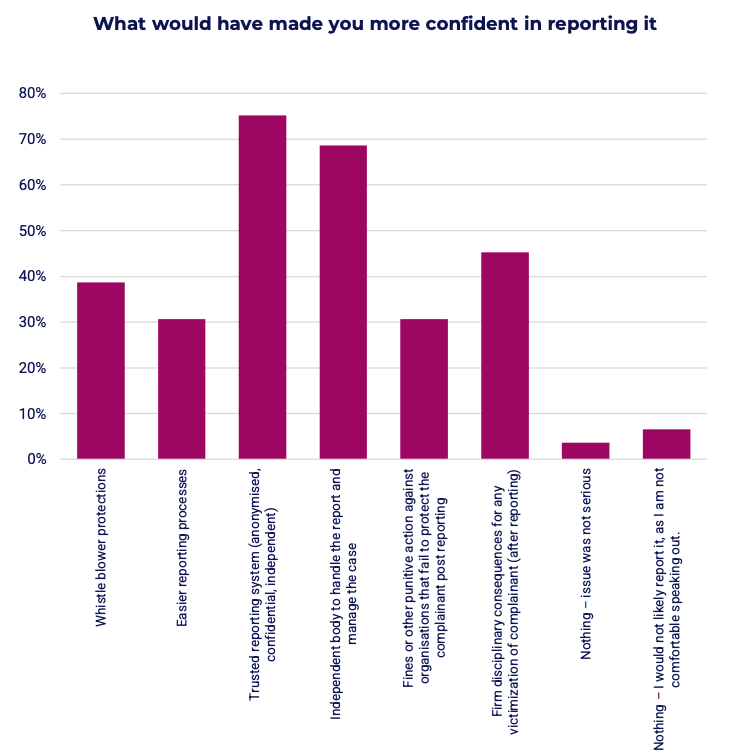

What would make it easier to report?

Focus group participants identified the importance of addressing systemic issues as a fundamental component to encouraging reporting. Specifically, they cited a need to diverge from traditional “topdown” organisational cultures that create the power imbalances that restricts an open, accessible culture and allows trusted reporting.

“The process is opaque and answers to questions vague. Things have been handled behind the scenes and no elaboration is given, simply “it’s confidential”.”

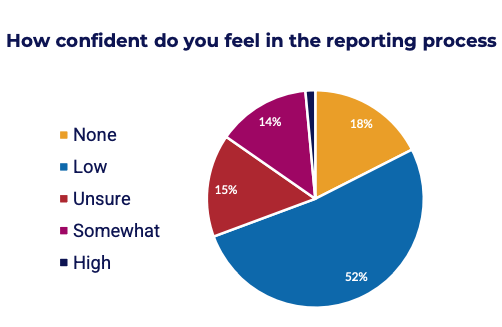

How confident did you feel reporting?

69 percent of respondents felt low or no confidence in the reporting process and only 1 percent have a high confidence in the reporting process.

Focus groups revealed that a major concern and barrier to reporting was the potential impact of reporting on career or job security.

Focus group participants felt that perpetrators avoid accountability in the reporting processes. Where perpetrators do face any consequences, these are usually limited to apologies or actions that are not visible to victims.

Focus group participants believed that sham investigations are the norm. For example, in instances where preliminary steps were taken after reporting, key information was omitted as a result of managerial bias.

Data by the WBI indicates that sham investigations represent an estimated 46 percent of total responses by employers, reinforcing a consensus that concludes reporting is a “waste of time”. iv

Participants also indicated that white leadership is a contributing factor to the lack of trust in reporting processes. Women of Colour feel safer and are more inclined to report to representative senior leaders that they believe will understand and validate their experiences. However, participants reported anecdotally that whilst the proportion of women in senior management roles has increased in recent years in Australia, Women of Colour are still widely underrepresented.

“Because it can be quite covert, it can be very micro in its form; it can cut you off from your peers and others. You don’t say it. And in speaking out, you know you are wrong”

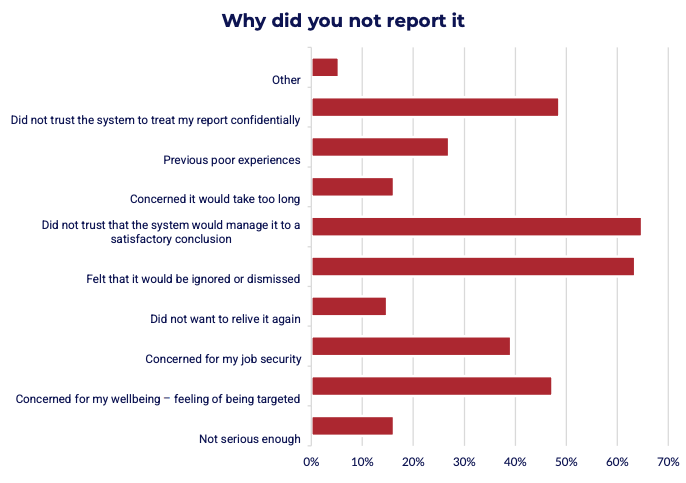

Why did you not report?

Participants cited that “they did not trust that the system would manage it to a satisfactory conclusion” (65 percent) of respondents or felt “that it would be ignored or dismissed” (64 percent) as the top two reasons for not reporting. Job security, lack of trust in the system to treat the report confidentially, or a concern of being targeted, were the other main responses.

The results of the survey overwhelmingly pointed to a lack of trust in the systems and processes in place to manage reporting of racism, discrimination, or race-related bullying. Concern for their job security or being targeted indicates a fear of reprisals.

Summary of Recommendations

Creating safer workplaces requires long-term strategy, funding and active coordination and participation across all levels and stakeholders.

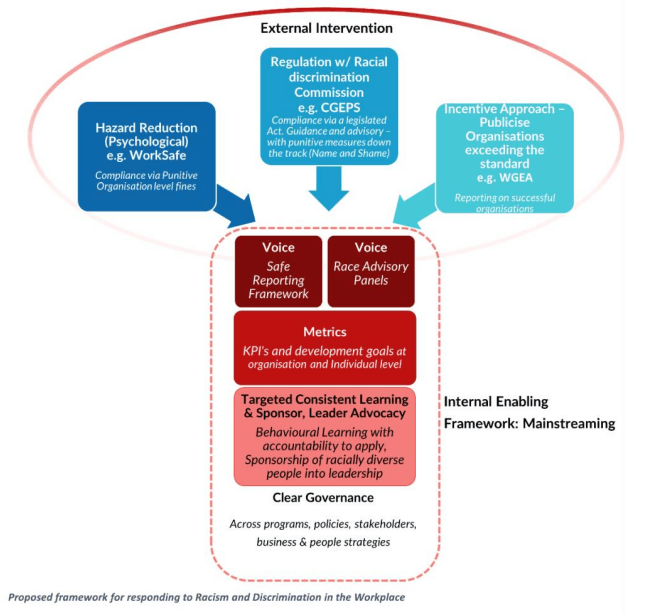

This section presents recommendations based on three potential interventions that can be taken by organisations, WorkSafe, CPSU and other regulatory bodies; to reduce racism and discrimination in the workplace.

The “External intervention” approaches are designed to support and reinforce an “Internal Enabling Framework”, which is necessary to support the change and create a cultural shift in VPS workplaces. This framework, based on the strategy of “Mainstreaming”, can be summarised as Voice, Metrics, and Targeted Behavioural Learning & Sponsor Advocacy, and is underpinned by a strong Governance Structure. Gender mainstreaming has been a foundational strategy for achieving gender equality objectives in Sweden’s government agencies since 1988. This process involves changes to long-term development programs to promote gender inclusion and equality across all levels whilst simultaneously addressing barriers to reporting channels. Due to the demonstrated efficacy of this strategy (noting: Sweden’s strides in establishing gender equality in their public services), our recommended framework has been adapted to address barriers associated with racial discrimination.

External Intervention

We engaged executive and senior Anglo leaders to ask them what would help them lead change and they all agreed that some external intervention would help all leaders, not just some who were inclusive and intentional already. We have summarized this into four approaches [three were presented to leaders and they came up with a ‘balanced approach, a blend of two of the approaches].

- Incentive Approach: to enable data collection, goal setting at a macro level and guidance to achieve key performance goals and indicators.

- Hazard reduction [Punitive] (Psychological safety) approach: to eliminate incidents of racism.

- Racial Discrimination Commission [External Agency Approach]: to establish a comprehensive framework that supports all workplaces to eliminate systemic discrimination.

- A balanced approach (i.e., both incentivising and punitive) with materials, tools and resources for employers to support implementing required the change as the gaps are evaluated and progress is tracked to reducing and eliminating racial discrimination.

“Incentivising leaders is the way to get traction – It has to be in their PDP otherwise we won’t get action.”

Internal Enabling Framework [Mainstreaming]

Voice

We recommend evaluating all ‘voice mechanisms’ whether it be through employee resource groups, employee surveys, employee assistance programs; to assess whether data collection and narratives are deriving the Truth about how employees think and feel. We recommend improving reporting and complaints procedures and innovating this space to ensure that there is some form of anonymous reporting to capture lead data instead of lag data [when someone reports an incident formally]. We also recommend race advisory panels, where employees sit in a quorum or board-like group to assess and advise on progress with the reduction and elimination of racial discrimination.

Metrics

We recommend that leaders and staff all have development goals at least to improve their racial literacy and to improve their ability to reduce and eliminate racism. Leaders in particular may be open to having this tied to their key performance indicators and not just from a ‘zero reports metric’ but also from a proactive, preventative action stand-point to showcase the positive duty of care.

Targeted Behavioural Learning and Sponsor Advocacy

Overall, Australian workplaces have a low racial literacy, and understanding of both race and racism. We know the nature and context of racism in Australia is covert rather than overt and is everyday casual racism that builds and is pervasive. The best method we have executed is targeted behavioural learning, where everyday scenarios are deidentified to showcase, opportunities for the reduction or elimination of racism from both the bystander, person experiencing racism and person enacting racism, position. Learning and application needs to be accountability checked, so that learners apply what they have learnt back into the workplace. This learning can be incorporated into a development goal and key performance metrics. This coupled with public, positive sponsor advocacy [where a leader uses their personal and positional power] to influence both the representation and inclusion of racially and ethnically diverse people, fast-tracks this enabling environment towards mainstreaming.

Governance Structures

We recommend that all strategies, business, people, workforce planning, diversity and equity inclusion plans are synergistic to form a strong governance framework. All too often we see the gaps and silo-ed way these strategies, plans, policies, programs of work counter each other, which slows progress for all diversities. The way key stakeholders work to influence both the internal and external environment is also a key governance consideration – all too often, the structures are sound, but the people and leaders in it, are not in synch.

Conclusion

Women of Colour cultural and psychological safety in all their employment experiences require an intersectional lens, of understanding both racism and sexism at work. This is not a silo-ed or narrow view, we know that when we make it safe for women of colour, all women benefit. Both the external interventions and internal interventions are key considerations for all people at work experiencing racism. The nature and context of racism, as well as its history for racially and ethnically diverse, Non-Indigenous peoples is that it has been wrapped in the positive notion of multiculturalism, which makes it challenging and unsafe for people to raise their voices to call out racism. We recommend that organisations don’t rely on formal reporting [which we know is low especially on racism], but that there is an organisational and leader response that is proactive and preventative when it comes to reducing and eliminating racism at work.

Endnotes:

i CPSU Survey analysis (Not included in the appendices in this report due to confidentiality

ii Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989; Vol. 1989, Article 8; 1989.

iii Potter RE, Dollard M, Tuckey MR. Bullying and harassment in Australian workplaces: results from the Australian workplace barometer 2014/15; 2016.

iv Namie, G. 2017 WBI U.S. Workplace Bullying Survey. [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2021 May 4]; Available from: https://anannkefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2017-WBI-US-Survey.pdf

About the Author

MindTribes is a team of expert diversity consultants committed to transforming workplaces through tailored diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) strategies. They specialise in creating safe, inclusive environments with services like DEI strategy development, anti-racism training, and leadership programs. MindTribes combines research-driven insights with practical solutions to address systemic inequities, build allyship, and empower organisations to embrace cultural diversity. Our holistic approach helps businesses foster belonging and achieve sustainable, positive change.

About the Author

MindTribes is a team of expert diversity consultants committed to transforming workplaces through tailored diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) strategies. They specialise in creating safe, inclusive environments with services like DEI strategy development, anti-racism training, and leadership programs. MindTribes combines research-driven insights with practical solutions to address systemic inequities, build allyship, and empower organisations to embrace cultural diversity. Our holistic approach helps businesses foster belonging and achieve sustainable, positive change.